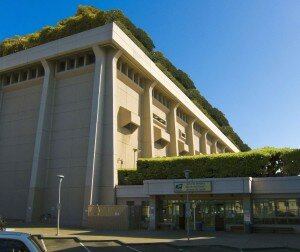

The West Oakland, CA, post office as it is today, left, and as the author imagines it with a rooftop refuge. (D.C. Carr/USFWS)

As South Bronx eco-entrepreneur Majora Carter was explaining her block-by-block green-the-ghetto philosophy to a plenary session at the Conserving the Future conference in Madison, WI, last July, the following appeared on the big Twitter-feed screen next to her:

@dc_carr

Urban refuges? Imagine a partnership-based NWR entirely on the roofs of urban buildings #visionconf

I posted that tweet. What was I thinking? Allow me to tell you.

If we, in the Refuge System, want to connect people with nature, we must bring them to nature or nature to them. With urban populations, we could do a little of both. As we implement Conserving the Future recommendation 13 (create an urban refuge initiative), we could take advantage of existing urban green spaces and we could seek to encourage development of new pockets of nature in the urban jungle.

My neighborhood in West Oakland, CA, is, like the South Bronx, a landscape of brick and concrete surrounded by the skeletal remains of industry. The birds that sing are starlings. The flowers that bloom are thistles. Little of this landscape resembles what we think of as a wildlife refuge. Indeed, even if some slice of the cityscape were as desirable as a traditional refuge, the land’s purchase price might be cost-prohibitive.

As Carter told the Madison conference, under her initiative young people in the South Bronx are helping to transform tarpaper rooftops into gardens. These rooftop gardens take full advantage of available space and sunlight to create oases for birds, plants and people.

“I believe that you shouldn’t have to leave your neighborhood to live in a better one” is Carter’s motto. She recognizes the importance of ingenuity in creating a healthier environment. She envisions turning urban blight into appealing, green-roofed neighborhoods. And she knows, as do I, that in these difficult economic times there are plenty of unemployed hands who would gladly take on paid work to help do it.

In West Oakland, the unemployment rate is more than double the national average. I know the much same is true in other urban areas. My neighborhood has long been plagued by abandoned or deteriorating buildings, poor infrastructure and the smell of hopelessness in the air.

The community’s centerpiece is a huge, flat-topped postal facility built as part of a 1970s urban renewal project. It still evokes hard feelings because many residents were relocated and several Victorian house-filled blocks were flattened for its construction. That part of West Oakland, next to a closed army base, is littered with flat-roofed warehouses. There are acres of tarpaper or tar-and-gravel roofs. When you walk through the neighborhood, no birds sing. The air is filled with the roar of tires on asphalt. When the wind blows, it carries no fallen leaves. The breeze is weighted with the discarded candy wrappers and soda cans.

Imagine trees and gardens on the rooftops of the postal facility and the dozens of similar buildings nearby. Imagine if these gardens all were managed together as one rooftop wildlife refuge – a sanctuary for neotropical birds at the edge of San Francisco Bay. Imagine local children walking just blocks from their school to the West Oakland Rooftop Refuge for a science lesson or to assist biologists banding birds. Imagine the habitat management and environmental education internship opportunities for local high school students. All of this could be right here in this neighborhood. Now imagine it in your neighborhood.

That’s what the tweet meant to say: If we in the Service want people, especially young people, in places like West Oakland and the South Bronx to believe that conserving nature makes a difference, we’re going to have to meet them partway.

- D.C. Carr

D.C. Carr is a visitor services planner in the Service’s Pacific Southwest Region office in Sacramento, CA.

10 Comments in this post »

RSS feed for comments on this post. | TrackBack URL

This is a very cool idea, DC. I hope it catches on somewhere.

As always DC you see the possible in the most impossible looking locations. Love the idea and hope the vision will become reality and we are able to resurrect the nature we have suppressed and along with it – the connection of people to nature!

Great piece, DC. My last trip to NYC in 2008, I was thinking the same thing. On my way to Shea Stadium, looking at all those roofs. I’m also a big fan of Carter and her work, even before Vision. Short of a national initative though, we need a grassroots effort. Aren’t many of our field stations working with schools already? How about getting the Friends to write a grant, getting the school to identify an urban partner who wants a green roof (incl. churches, businesses, etc.) and making it happen? Perhaps the urban implementation team could get us some traction here. Some kind of recognition from the Service of these mini-refuges? SO MANY grant opportunties exist, they are almost too numerous to mention – stormwater retention/filtration, environmental justice, remediation, etc. This project sells itself. We need buy-in from Service leadership and boots on the ground to make it happen. Actually, we already have the boots on the ground – we just need to think outside the box/refuge!

P.S. You know what else is gaining traction? Urban farming. Met this guy at a career panel discussion last night at the U of MN: http://stonesthrowurbanfarm.wordpress.com. We need to snap up the green roof market fast – because if we don’t, these urban farmers surely will! (something tells me they don’t have the bureaucratic hoops to deal with LOL)

Love this blog!! relevancy=meeting people where they are at.Just had a meeting with GroundWorks USA- working to build conservation stewards in urban environments- and it was inspiring to hear their success stories with the Park Service. I could see the Refuge System taking a similar approach.

Ann Marie: Urban farmer is rejuvenating blighted parts of cities like Detroit and Buffalo, too.

Farming, not farmer

Saw this recently and wanted to add it to the conversation: http://vimeo.com/57478544. As I mentioned earlier, the urban farming movement is snapping up roofs. Time to mobilize!

Boston’s Green Roofs: The Benefits of Farming and Gardening Up in the Sky

Hi all, here every one is sharing these familiarity, therefore it’s pleasant to read this webpage, and I used to go to see this blog every day.

If you are in Roofing you recognize that there’s a lot of recourses which might be full nonsense, fortunately your site is just not one of these websites, i like your content very much, keep up the good job